A while back, I asked for readers to contribute data on the number of applications and interviews they put in for faculty jobs (or equivalent, e.g., government scientist, full-time scientist at an NGO, etc), and now the long-awaited results. Hang on to your seats, job-seekers (and hiring committees), here we go (and pardon my hastily-created figures).

Basic demographics

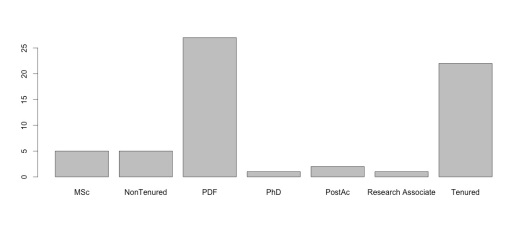

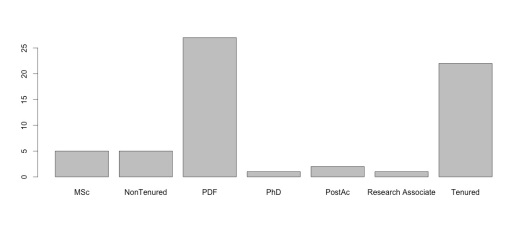

There were 63 respondents, and I didn’t collect data on age or gender. Most respondents were biologists (54%) or ecologists (21%), and nearly all were in some field of science (hello, dear Science Policy reader!).

Of those, 27 (43%) were my fellow postdocs, 22 (35%) were tenured faculty, 5 were non-tenured faculty, and there were 6 graduate students (5 MSc, 1 PhD), 1 research associate, and 2 folks that have left academia (Post-Ac). That said, my further analyses were restricted to postdocs and tenured faculty (which were the career stages I was most interested in to begin with), and I didn’t look at differences among fields.

Applications

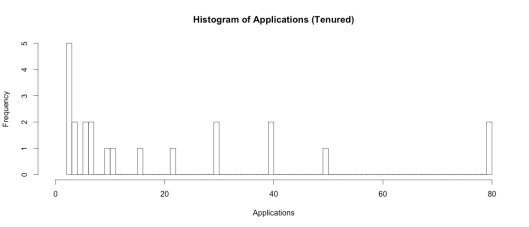

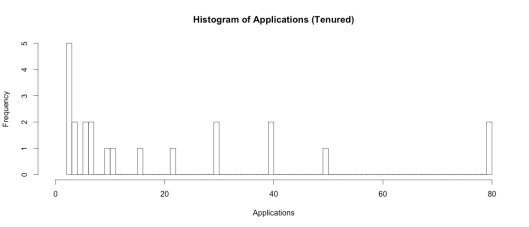

First, off, the ever-present question looming over postdocs is “how many applications do I have to prepare?”. Looking at tenured faculty responses, the median answer is about 8.5 (1st quartile: 4; 3rd quartile: 30), but there was obviously a huge range.

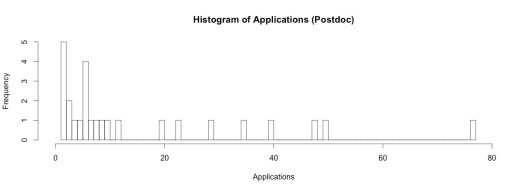

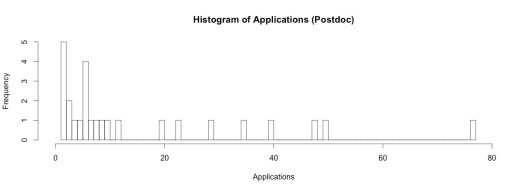

And how do postdoc respondents compare? Well, by all accounts, we’re almost there! (median: 6.5 applications; 1st quartile: 3; 3rd quartile: 22).

If we (incorrectly, I might add) use the mean ± SD to compare with my NSERC postdoc exit survey, there are some interesting similarities. The NSERC survey found respondents submitted 15 ± 20 applications. Tenured faculty responding to my survey had 20 ± 24, and postdocs 16 ± 19.

It’s important to note that the number of applications isn’t really a good metric of the job market. Some people are more selective in their applications. The advice I got as a grad student was to apply for everything (I don’t necessarily think that’s a good strategy). And as I’ve discussed before, job search strategies between Canadians and USians differ quite significantly, and likely owing to the sheer number of institutions in the US (>4000) compared with Canada (~100).

But let’s soldier on, shall we?

Interviews

Ah, the academic interview. That glorious 1-3-day excruciating event during which your every move is critiqued silently (wait, you put butter on the scones before jam? Tsk tsk), and you over-analyze every decision (“Should I get the soup for lunch? What if I spill it on my one set of dress pants? Is it too expensive? Are we even having appetizers? Oh god!” was an actual thought I had at my first on-site interview. Tell me that’s a healthy reaction).

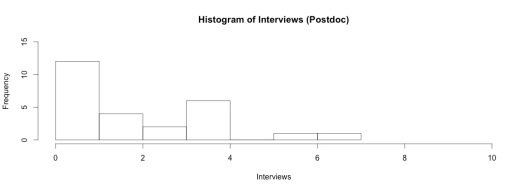

But nearly-overpowering anxiety aside, how many times did tenured faculty have to go through this arduous process? The median response was 3 times (1st quartile: 1, 3rd quartile: 5), and no more than 8.

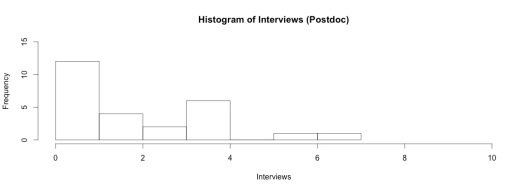

And just like the job applications, postdocs are following close behind – median: 2 (1st quartile: 1, 3rd quartile: 4; max: 7). So as a population, we seem to be “almost there”.

In the NSERC postdoc exit survey, respondents had 3 ± 7 interviews. Converting my survey numbers shows faculty with 3 ± 2, and postdocs with 2 ± 2. So it seems the NSERC respondents were considerably more variable (but then again, their range was 1-99, and I find 99 interviews to be a bit suspect).

What’s evident is that while a bunch of people are successful at landing a job on their first interview, most aren’t. And again, this doesn’t account for job offers that candidates decline (for various reasons).

The Application:Interview ratio

This brings us to the main point of my original post – how many applications must one complete per interview? If you recall, the NSERC group showed ~5 (which I thought was low). Survey says …

Tenured faculty (who, let’s remember, started their jobs between 1 and ∞ years ago) submitted a median of 5 applications for every interview (1st quartile: 3, 3rd quartile: 7). For comparative purposes, that’s a mean of 7 ± 7. But also quite obvious is the long tail to the data.

And what about postdocs (75% of which were currently looking for work in this survey)? We’ve submitted a median of 5 applications for every interview (1st quartile: 2, 3rd quartile: 9).

So it turns out that while 5 applications/interview is “average”, there’s a lot of variation. The big question, though, is whether this is different between tenured faculty and postdocs. A basic two-sample t-test says it isn’t (p = 0.96), and ditto for the less powerful non-parametric Wilcoxon ranked sum test (p = 0.70). But insert the usual caveats of low sample size, and lots of confounding variables (age, gender, field, country, …) here.

The bottom line

A significant chunk of postdocs’ time is spent applying for jobs, and this process could be streamlined considerably. And while some seem to land a faculty job with relative ease, it’s a slog for many others (submitting up to 80 applications in total, and >15 for every interview). At the same time, though, the number of PhD job seekers is rising at a much faster rate than faculty jobs have been created. My survey didn’t account for what kinds of jobs folks applied for, and there’s an increased awareness of “Alt-Ac” or “Post-Ac” jobs. And it also includes applications for postdoc positions.

The postdoc career stage seems to be the pinch-point for academics in Canada. And it’s very easy to get discouraged when so many applications (that take considerable effort) don’t pan out. Part of the solution would be increased support for postdocs through NSERC and similar programs, and a reduction in the insane amount of duplication that goes into job applications. Faculty search committees can also help, by not requiring letters of reference until the long/short-listing process, for example, which would save everyone time.

But lastly, and perhaps most importantly, it’s important for postdocs to have a good support network. The job application process is fraught with giddy highs and depressive lows, all in a short period of time. Whether this is a faculty member, other postdocs, labmates, friends, and/or family, having a group of people with whom you can share the exciting news about interview requests, or the crushing news that you weren’t short-listed will only help. The adage that “something will come up eventually” will start to grate on your nerves, but those who speak it mean well. And what “comes up” might not be a tenure-track faculty job, though it can still be fulfilling.

So once more unto the breach, dear postdocs, once more.

UPDATE (1 Dec. 13) – check out this post, and the figures that show the career trajectories in science, and the significant amount of attrition. <1% of those who start in science end up in the professorial route (though 30% might consider themselves “early-career researchers”). It also has considerable resources for non-academic jobs (ht Grant Jacobs)