Picture this: it’s the Age of Enlightenment, and you’re a budding young “natural philosopher” (what we now call a scientist) sitting in your study. All through the summer, you’ve observed swallows, cranes, thrushes, and more in the local area, but very slowly they start disappearing until, in roughly early November, they’re gone. So what happened to them?

Aristotle and his students believed that swallows hibernated, for example. Or that the birds that arrived for the winter were the transmuted birds they had seen all summer long.

A 1703 pamphlet* called “An Essay toward the Probable Solution of this Question: Whence come the Stork and the Turtledove, the Crane, and the Swallow, when they Know and Observe the Appointed Time of their Coming” postulated that when birds disappeared in the fall, they went very far away. About 384,400 km away in fact. To the moon.

It seems rather obvious to us now that birds (and many other animals) migrate – they breed in one area, and “winter” in another to make use of the seasonal abundance of productivity at higher latitudes in the summer months. The Arctic Tern has the longest migration of any animal yet recorded: averaging 71,000 km/year from Greenland to Antarctic and back. If the average Arctic Tern lives 20-25 years, that’s about 1,500,000-1,750,000 km in their lifetime. Truly incredible.

These Arctic Terns breeding in New Brunswick fly to the edge of the Antarctic ice sheet for the “winter”, so they actually experience perpetual summer.

And huge congregations of migratory birds, like Snow Geese, can completely cover the landscape for kilometres at a time as they move in the millions.

But our 18th-century natural philosophers didn’t know this yet.

On May 21st, 1822 on the Bothmer Estate in Klütz, Mecklenburg, Germany, someone shot a White Stork. You see, this was the 2nd time someone tried to kill this particular stork, but the first time didn’t go so well (for the hunter), and the stork got away.

With a spear in its neck. It was an “arrow stork” or “Pfeilstorch” in German. And it was the key to one of the most amazing, elusive, and important parts of animal life history: migration.

When the Pfeilstorch was taken to the University of Rostock (where it still “lives”), the spear was immediately recognized as something not from Europe. In fact, it was from Africa. A stork flew from Africa with a spear through its neck, only to be shot in Germany.

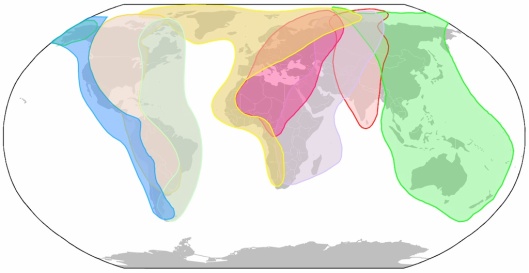

We now know that White Storks winter in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly savannahs from Kenya to Uganda, and as far south as Western Cape, South Africa, and not on the moon. In fact, most bird migration falls along several well-known “migratory flyways”.

Before this, though, we had no idea where storks went in winter. Other popular theories included hibernation (in locations unknown, including underwater), and the aforementioned lunar journey. There are 25 known Pfeilstorchs in natural history collections, mostly in Germany and west-central Europe.

But given that spears are used less commonly these days for hunting of birds (and it’s pretty darn hard to spear a swallow), how do we study bird migration now?

In 1899, Dutch teacher Hans Mortensen began putting aluminum rings on the legs of birds that he captured. He inscribed the bands with his address, and instructions to contact him should the band be found. In North America, bird banding (as it became to be known) started in 1902 when Paul Bartsch banded Black-crowned Night-herons in the eastern US. Now, banding is coordinated through the US Bird Banding Lab and Canadian Bird Banding Office, banders apply for permits, and keep an inventory of myriad band sizes for any species in North America. There’s also the North American Banding Council, which oversees best practices and training for banders (and I happen to be on the board).

Bands, for example, helped us discover where Chimney Swifts spent the winter (PDF of the 1944 USFWS press release), 69 years ago this month.

In addition to bands, telemetry gear that senses light levels can be used to track migration in birds as small as Barn Swallows, which we now know spend their winters from southern Mexico to central Brazil and northern Argentina.

This small geolocator deployed in Saskatchewan will calculate this Barn Swallow’s position each day, and when we recapture it in 2014 and download the data, we can see where it spent the winter (likely Mexico or Colombia).

But there’s one thing that Aristotle, natural philosophers of the Enlightenment, 19th-century German marksmen, and us today can agree on – bird migration is one of the most amazing parts of our natural world.

*I haven’t yet found a copy myself, so can’t say if this story if apocryphal or not, but it seems to be well-cited by reputible sources

Pingback: Friday links: an accidental scientific activist, unkillable birds, the stats of “marginally significant” stats, and more | Dynamic Ecology

Great post. It is nice to know the story behind migration undestanding. And please, if you find a copy of the 18th century article, let us know.

Pingback: L.AMA.N.T.IN.I #3 | IL VOLO DEL DODO

Pingback: Touched by Science | ScienceBorealis.ca Blog

Pingback: FAQ, and answers thereto « The Lab and Field

Pingback: Science online, migrate me to the moon edition | Jeremy Yoder

Pingback: Migrations to the Moon: When Common Sense Flies South |

Hans Mortensen was Danish, not Dutch. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Christian_Cornelius_Mortensen

Pingback: 2014 by the numbers | The Lab and Field

Pingback: Sailors and Swallows: Clearing up a Tattoo Mystery | A-wing and A-way

Pingback: 2015 by the numbers | The Lab and Field

Pingback: FAQ, and answers thereto (Christmas 2016 edition) | The Lab and Field

Pingback: 2016 by the numbers | The Lab and Field

Pingback: FAQ, and answers thereto (Christmas 2017 edition) | The Lab and Field

Pingback: 2017 by the numbers | The Lab and Field

Pingback: 2018 by the numbers | The Lab and Field

Pingback: 2019 by the numbers | The Lab and Field

Pingback: 2020 by the numbers | The Lab and Field